What is the Broken Window Theory?

Envision an urban landscape, slightly worn down by time, where amidst the concrete and old brick walls a single window stands shattered. This imagery powerful in its simplicity, introduces us to the broken window theory. This principle is pretty intriguing, it says that when things look messy or neglected, it can lead to even bigger problems like serious crimes or bad behavior. At first glance, it might just seem like a simple observation, but it’s actually made a big impact in criminology and studies about society.

Curious why? Well, this idea goes beyond just the idea of a broken window. It tells us a lot about how people act, what society thinks is normal and what can happen when people think no one cares. James Q. Wilson who articulated the theory once said: “Disorder and crime are usually inextricably linked, in a kind of developmental sequence.” This connection pushes us to think about the cities we inhabit and the intricate webs of human interactions within them.

Historical Origins

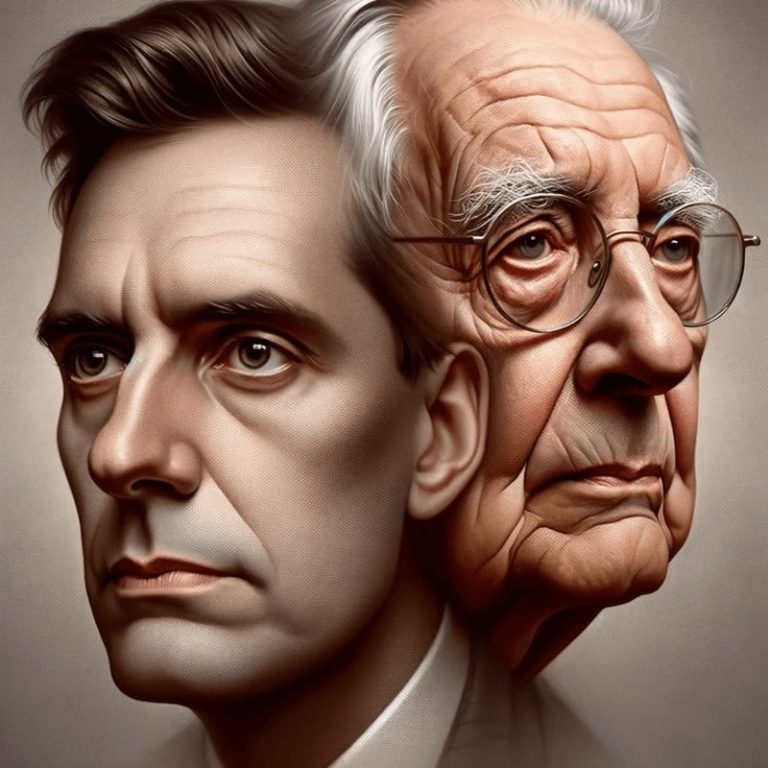

Journey back to 1982. The world was evolving, but within the pages of a landmark article, a model emerged, intertwining urban decay with burgeoning crime. This revolutionary idea, coined as the “broken window theory,” was the brainchild of James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. Their collaborative exploration painted a tapestry of urban narratives wherein unchecked minor disorders snowballed into major criminal activities. But rewind a little further. Before Wilson and Kelling’s elucidation, Philip Zimbardo, a prominent psychologist, had already sown the concept’s first seeds.

Through a daring experiment involving abandoned cars in the 1960s, he demonstrated the rapid descent of order into chaos when negligence became perceptible. Zimbardo’s pioneering efforts provided the foundation upon which Wilson and Kelling built, bridging the divide between psychology and criminology. This blend of minds and decades forms the bedrock of our understanding of urban disorder today.

The Core Concept of the Theory

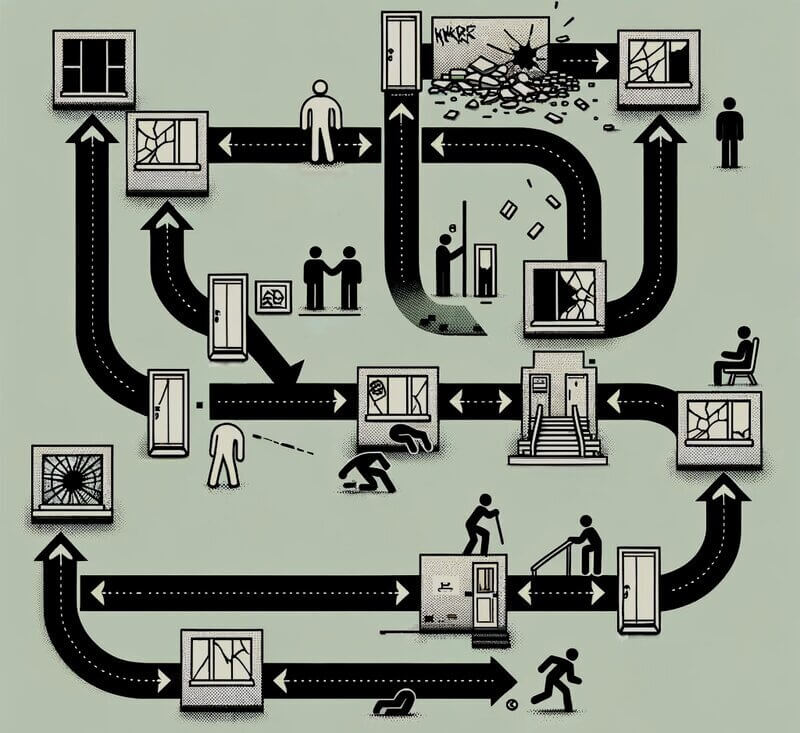

Delving deeper into the broken window theory unveils a universe of intricate connections and nuanced propositions. At its heart, the concept encapsulates the premise that seemingly minor neglect—like a singular broken window—can act as a catalyst for a more pervasive sense of disorder. Left unattended, this minute sign of decay broadcasts a message: no one cares. Consequently, it begets an environment where antisocial behaviors thrive.

But what exactly constitutes “physical disorder” in this context? Picture a neighborhood: unkempt front yards, graffiti-sprayed walls, and the eponymous broken windows. These are not merely urban blemishes; they’re visual cues. They hint at a community’s indifference or inability to maintain order, signaling potential criminals that their acts might go unnoticed or unchecked.

Two principal disorders emerge within this notion’s purview: social and physical. While physical disorder embodies tangible degradation—those shattered windows or litter-strewn alleyways—social disorder delves into the realm of human behavior, such as public drunkenness or aggressive panhandling. The synergy between these disorders creates a reinforcing loop, amplifying the sense of neglect.

So among the myriad of criminal acts, which one signifies the first “broken window”? It doesn’t have to be a heinous act. Even a simple act of vandalism, if overlooked by everyone, could spiral into more egregious crimes, driven by the perception that the area is unsupervised.

Core Concepts at a Glance:

- Physical Disorder: Manifestations of tangible urban decay (e.g., dilapidated buildings, graffiti).

- Social Disorder: Observable unruly behaviors in public spaces, suggesting lawlessness.

- First Broken Window: Typically a minor crime (like vandalism), serving as a bellwether for potential escalation.

The Broken Window Theory in Various Contexts

While the theory arose from urban narratives and criminological discussions, its tendrils stretch into diverse terrains. Its core premise, after all, transcends mere physical environments, shedding light on the profound interplay between neglect and behavior, surroundings and psyche.

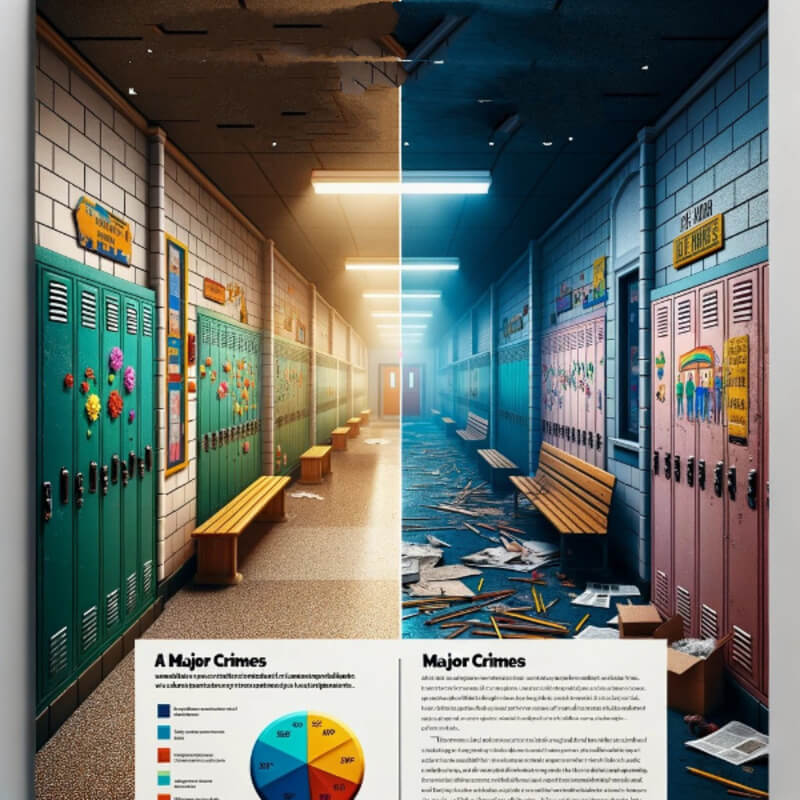

Imagine walking into a school. The walls are stained, lockers graffitied, and corridors littered. In such an environment, the very ethos of education can become overshadowed. This is the broken window theory at play in educational institutions. A disorderly, neglected school environment can dampen the morale of both students and teachers. It subtly communicates that if the physical surroundings aren’t valued, perhaps academic endeavors aren’t either. As academic commitment wanes, truancy and behavioral issues may escalate. The message is clear: aesthetics and ambiance mold mindsets.

But, how does this idea unfurl its effects? It operates on perceptions and interpretations. A single unchecked misdemeanor, like a shattered window, acts as a precedent. If minor transgressions aren’t addressed, it nudges societal norms, making larger transgressions seem less taboo. Over time, this creates a cascade of increasing lawlessness.

In criminology, this thesis unveils the relationship between environment, crime, and community vigilance. Areas marked by visible neglect become hotbeds for crime, not necessarily due to inherent malevolence of residents, but because of the perceived absence of accountability. It’s the ambiance of impunity that lures criminal behavior.

Segueing into policing, this thesis has profoundly influenced strategies. Proponents argue that by addressing minor offenses proactively—be it graffiti, loitering, or fare evasion—it’s possible to thwart the escalation into serious crimes. The idea isn’t just punitive but preventative. By reinforcing communal norms and showcasing active vigilance, a sense of order is restored. However, it’s worth noting that while many police departments have found success with this approach, it’s imperative to strike a balance, ensuring that minor offenses don’t lead to disproportionate penalties or discriminatory enforcement.

Diverse Contexts at a Glance:

- Schools: An orderly environment fosters academic dedication.

- Operational Mechanism: The proposition functions by shifting perceptions and societal norms.

- Criminology: Highlights the ambiance-crime nexus.

- Policing: Focuses on proactive intervention for minor offenses to prevent major ones.

Connection to Literature and Research

The evolution of a concept isn’t confined to academia or policy alone. Sometimes, it becomes a part of our pop culture, making a mark in our shared memories. Such is the trajectory of the ‘broken window theory’, which found resonance in Malcolm Gladwell’s seminal work, “The Tipping Point”.

Gladwell’s book, which dives deep into how trends catch on, gives the concept a special spotlight, highlighting how it plays a part in how behaviors spread. He looks at those tipping points, those little moments that make a big difference, turning small patterns into big trends. And right there, among his engaging stories, you’ll find our idea. Its essence is detailed in the context of New York City’s transformative approach to crime during the 1990s. By focusing on minor infractions, authorities believed they could, metaphorically, halt the contagious spread of crime.

Now, those seeking precise references might ask, on which exact page of “The Tipping Point” does Gladwell dissect this idea? While the specific page might vary across editions, it’s crucial to understand the essence over the enumeration. The book really brings out how the theory is key in understanding changes in society, hinting that tiny changes can lead to huge ripple effects.

Broken Window in Real Life

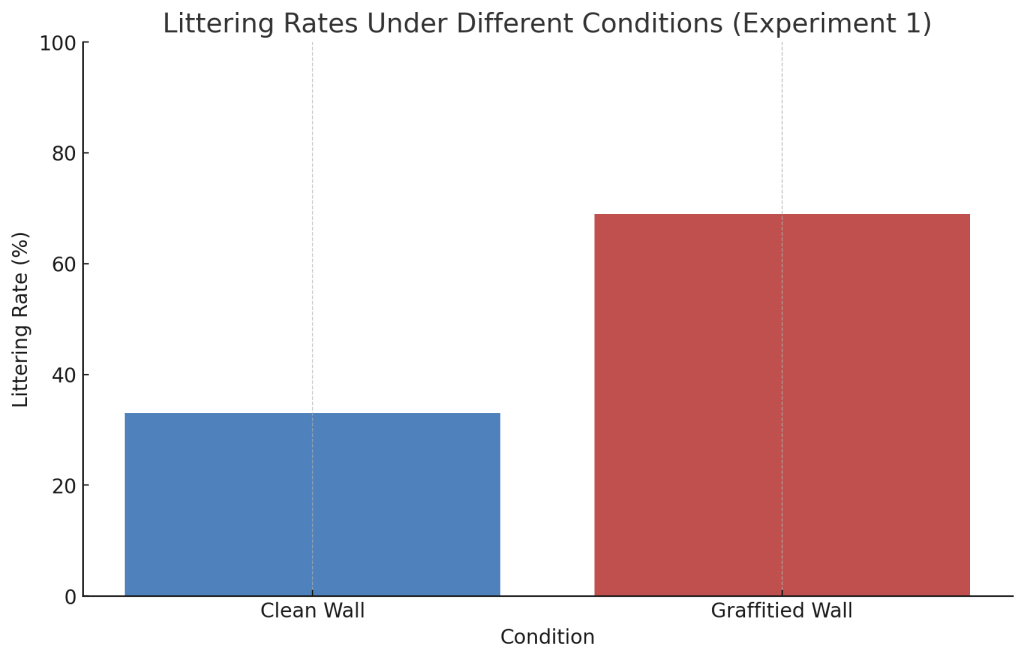

The six experiments conducted to test the Broken Window Theory are as follows:

- Littering and Graffiti: Conducted on a busy shopping street, researchers initially left a wall clean, attaching a holiday greeting card to parked bicycles. Only 33% littered. When the wall was covered in meaningless graffiti, 69% littered, indicating that visible disorder encourages norm violations like littering.

- Barrier Compliance: A barrier with a wide gap blocked a parking lot entrance, accompanied by signs prohibiting entry and bike attachment. With orderly conditions (bikes not attached to the barrier), 27% bypassed the barrier. When order was disrupted (bikes attached to the barrier), 82% did, showing that visible norm violations encourage others to disregard rules.

- Shopping Cart and Littering: In a supermarket parking lot, with an announcement asking to return shopping carts, no carts were present in orderly conditions, leading to 30% littering. When four carts smeared with grease were left around, 58% littered, demonstrating increased disregard for norms amidst visible disorder.

- Sound of Fireworks and Littering: In the Netherlands, using fireworks before New Year is illegal. Cyclists littered more frequently when they heard fireworks, suggesting that auditory cues of norm violations can also lead to increased littering.

- And the last, Petty Theft Provocation: A visible 5-euro note in a mailbox was the bait. In orderly conditions (clean mailbox, no litter), 13% of passersby stole it. When the mailbox was vandalized with graffiti or surrounded by litter, thefts increased to 27% and 25%, respectively, indicating that visual disorder cues encourage petty theft.

These experiments collectively demonstrate that visible signs of disorder, whether visual or auditory, can significantly influence people’s behavior, leading them to violate social norms and rules.

Literary Highlights:

- Title: The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell

- Core Argument: Minor changes can trigger significant societal shifts.

- The Link: Seeing crime through the lens of the broken window theory as if it’s a behavior that can catch on.

The Theory in Practice

In an expansive cityscape like New York, where skyscrapers shadow the narrow streets below, and yellow cabs are more ubiquitous than the sprawling greenery, policies and practices can dramatically shape urban dynamics. One such influential strategy was the adoption of the broken window theory by the New York Police Department. The doctrine’s guiding principle – that maintaining urban environments and curbing minor offenses can prevent larger crimes – found a proactive champion in the NYPD.

Officers armed with the newfound understanding of this postulate, began patrolling not just for glaring violations but for the minor ones as well – be it graffiti, public drinking, or fare evasion. The perception that these minor infractions were symptomatic of a deeper societal decay led to heightened vigilance. New York’s strategy? Target the first broken window. The NYPD thought that by stepping in early, they could prevent further issues and keep things orderly.

But let’s pivot for a moment. Picture an abandoned house, its windows shattered, the paint peeling off, and weeds reclaiming the porch. You might wonder, “Why bring this house into a chat about the broken window theory?” Well, this house is like a real-life example of the model – showing neglect, falling apart, and hinting at crime. When places, like old abandoned houses, look a mess, it’s like they’re shouting out that no one’s watching, making them perfect spots for trouble.

Now, while there’s some good to the idea, it’s not without its problems. A big one? How it seems to hit those with less money the hardest. Targeting minor offenses can sometimes mean that those on society’s fringes, who might lack resources or be in desperate circumstances, bear the brunt of the policing. Taking this route might just widen the gap between groups in society, leaving those already struggling even more out of the loop.

Even though using the principle in this way was a game-changer, it’s complicated. It’s a mix of doing good and facing some tough moral questions.

Critiques and Controversies

The ‘broken window theory’, while hailed as a revolutionary approach in urban policing, has not been without its critics. As the dusky orange hue of setting sun bounces off skyscrapers, intellectuals and activists fervently debate the theory’s merits and shortcomings. It’s here, amidst the cacophony of opposing viewpoints, that one might wonder: where does the theory falter?

For many, the very foundational premise of the theory is flawed. The assertion that minor infractions inevitably lead to significant crimes oversimplifies the intricate dynamics of urban crime. Can a mere graffitied wall, after all, spiral into a web of complex criminal activities? Some sociologists argue that the theory offers a myopic view, focusing on surface symptoms rather than deep-rooted societal issues like poverty or education.

“To equate a broken window with the genesis of complex urban crimes is to misunderstand the roots of societal decay.” – Dr. Eleanor Hughes, Sociologist

However, the critiques don’t just rest on academic grounds. Many grassroots activists assert the theory’s application can lead to discriminatory policing. By emphasizing minor infractions, law enforcement might disproportionately target marginalized communities, further exacerbating societal divides and mistrust.

Diving deeper, when posed with the question – “The broken window theory of crime is most consistent with which views?” – a myriad of answers emerge. Some perceive it as a testament to the ‘deterrence theory’, suggesting that visible policing and swift action deter potential offenders. Yet, others see it aligning more with ‘labeling theory’, where individuals become stigmatized due to minor infractions, pushing them further towards criminal behavior.

In the grand tapestry of criminology and urban planning, the ‘broken window theory’, with its shimmering accolades, also carries the weight of stern critiques. Understanding it, therefore, requires not just a linear view, but a multifaceted lens capturing its complexities and controversies.

Comparative Analysis

Amidst the sweeping narratives of criminology, the broken window theory stands tall, a monolith of sorts. Yet, where there’s a theory, shadows of its counterparts and misconceptions often lurk close by. Let’s embark on a journey, drawing parallels and underlining contrasts.

First, ponder on this: What would be the antithesis of the ‘broken window theory’? Perhaps a theory suggesting urban decay doesn’t inherently lead to crime or that meticulousness in managing minor infractions won’t curb major crimes. It’s a viewpoint suggesting a societal fabric so resilient that no single broken window could rend it.

Now, while our memory lanes meander with the broken window theory, a similarly named but distinct concept emerges – the ‘broken window fallacy’. This economic fallacy, with roots dug deep in 19th-century French economic thought, speculates that destruction stimulates economic activity. Think of it as breaking a baker’s window, leading to economic benefits for the glazier. While the broken window theory examines a cascade of social decay, the fallacy pivots around economic ripples from destruction.

Broken Window Theory Features:

- Cascading effect of neglect leading to crime.

- Emphasis on community vigilance.

Broken Window Fallacy Features:

- Economic spin from destructive acts.

- Misinterpretation of benefits.

In the cosmos of theories and ideas, distinctions, albeit subtle, matter. The broken window in one tale could lead to crime; in another, it’s a twist of economic fate. Such is the landscape where names might converge, but narratives diverge, painting a mosaic of human thought.

Legacy and Impact

In the grand tapestry of criminological thought, certain theories shimmer with the weight of their influence; among them is the ‘broken window theory’. When asked, “Who might be the minds behind this powerful notion?” the answer unveils a fascinating history. James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, both stalwarts in their domain, are celebrated as its architects. Their insights, once merely written reflections, eventually danced off the pages and into the realms of pragmatic implementation.

Strategically employing this theory as an anchor, the NYPD in the 1990s underwent a metamorphosis. Spearheading this transformative era? None other than William Bratton. He championed the belief that rectifying minor infractions could stem the surge of major crimes, a tactical paradigm shift that dramatically reshaped New York’s landscape.

But to zero down solely on its policing applications would be a truncation of the theory’s vast expanse. More than a strategy, it’s a mirror reflecting society’s intricate complexities. It asserts a poignant commentary: Neglect, even in its minutiae, can spiral, decaying the societal fabric and emboldening criminal tendencies.

So, where does this theory nest in the broader context of criminological paradigms? It’s ensconced within the environmental criminology framework. This perspective hypothesizes that environment, both physical and social, plays a pivotal role in the genesis and propagation of criminal behaviors.

From the bustling streets of NYC to the global stage, the legacy of the broken window theory is profound and enduring. It not only reshaped policing but also altered how societies perceived disorder, igniting dialogues that ripple through time.

Conclusion

In the annals of criminological thought and urban evolution, few theories resonate as loudly or as profoundly as the ‘broken window theory’. Its roots, deep and intricate, stretch beyond mere criminal patterns, shedding light on the larger societal tapestry. “Order and disorder are not separate entities but intertwined threads in the fabric of a community,” opines an eminent sociologist. This succinct statement encapsulates the theory’s core tenet: the often-underestimated power of small signs of neglect in forecasting societal decay.

But it’s not just criminology that bears its mark. Urban planners, architects, and community leaders alike have woven its insights into their strategies, reimagining cities as sanctuaries where every window, intact or broken, narrates a story. As we stand at this juncture, reflecting on its immense impact, the onus is on us. Dive deeper, explore more, and perhaps even join the community groups working tirelessly to rejuvenate urban spaces.

In the echo of shattered glass, the theory implores us to listen, understand, and act.

References

The journey through the multifaceted landscape of the broken window theory wouldn’t be complete without a meticulous acknowledgment of the intellectual foundations that supported our exploration. Navigating the realms of economics, sociology, and criminology required the wisdom and foresight of numerous scholars and practitioners. Below, we honor these contributions:

- Wilson, J.Q., Kelling, G.L. (1982). “Broken Windows: The police and neighborhood safety.” The Atlantic Monthly.

- Zimbardo, P.G. (1969). “The Human Choice: Individuation, Reason, and Order Versus Deindividuation, Impulse, and Chaos.” Nebraska Symposium on Motivation.

- Gladwell, M. (2000). “The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference.” Little, Brown.

- “Economic Considerations of the Broken Windows Theory.” (Year). Journal name.

For those with an insatiable curiosity, a deeper dive into the economic underpinnings of the broken window theory is recommended in “Economic Evaluations of Neighborhood Disorder: Implications, Challenges, and Opportunities,” found in the Journal of Urban Economics.

Remember, the pursuit of knowledge is an unending journey. Beyond these sources lie vast intellectual territories, uncharted and waiting for your inquiry. As you cite these works, ensure each scholar’s contribution is accurately represented, respecting the integrity of their intellectual labor.